TL;DR

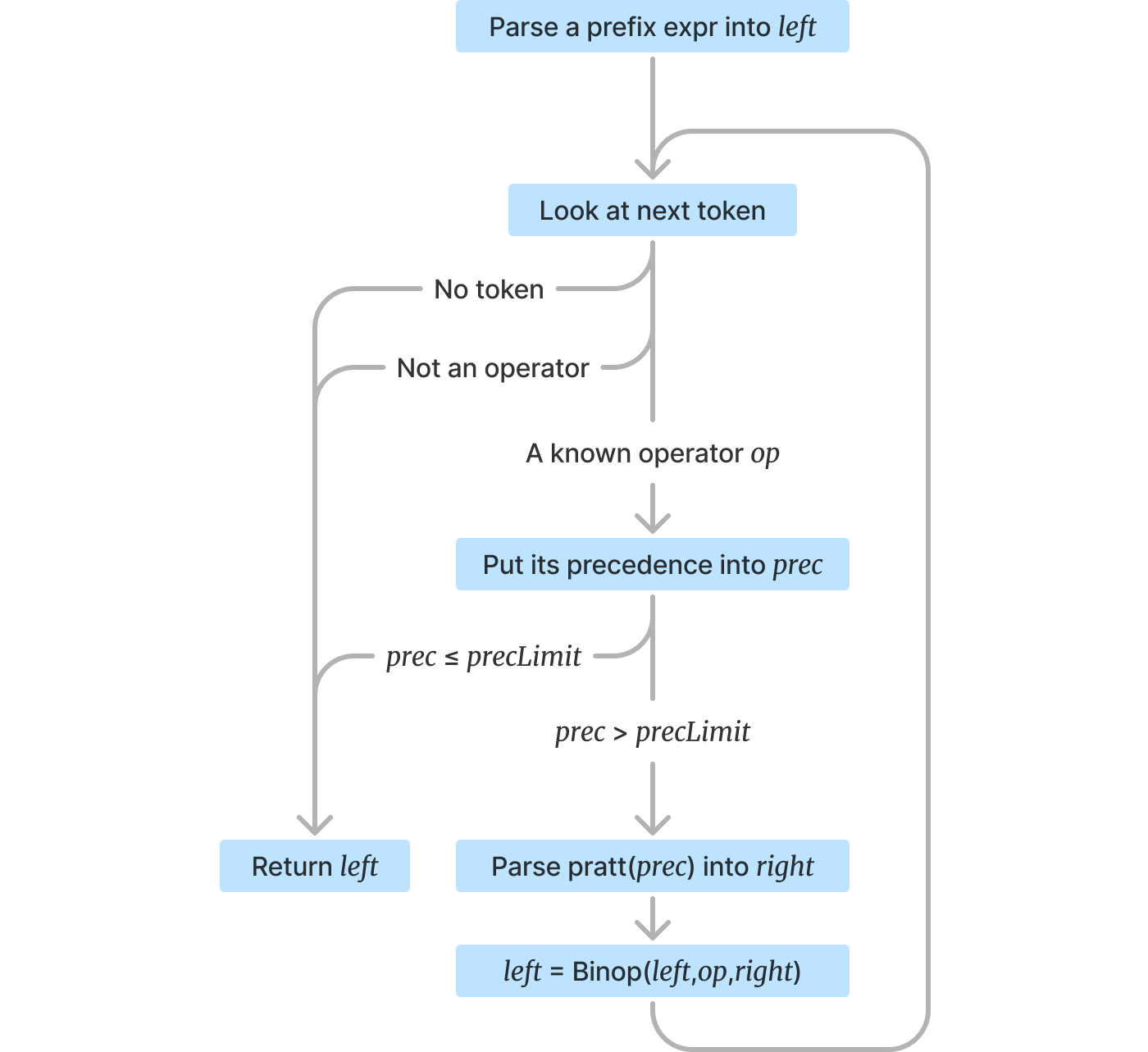

Here’s the algorithm for pratt(precLimit):

Here’s a minimal commented Pratt parser example in Elm.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Bob Nystrom’s article

- Overview

- Visual intuition

- Walk-through example

- Elm implementation

- Loose threads

- Conclusion

Introduction

Pratt parsers are a beautiful way of solving the operator precedence problem:

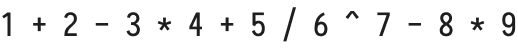

How can an expression like 1+2-3*4+5/6^7-8*9 be parsed to meet the expectations of your PEMDAS-trained brain? Where do you put the parentheses? What goes first?

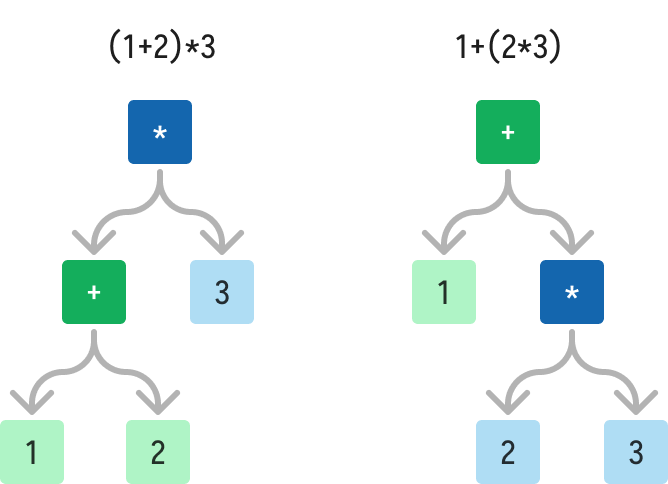

The underlying problem is the frequent ambiguity in combinations of operators. For example, how should the expression 1+2*3 be interpreted?

There are two options, each leading to a different value.

There are a few algorithms to solve this problem. Among them, my favorite is the Pratt parser—the most intuitive and declarative solution in my view.

Pratt parsers are an algorithm that takes your tokens ([1, +, 2, *, 3]) and a table like:

| Operator | Precedence |

|---|---|

| + | 1 |

| - | 1 |

| * | 2 |

| / | 2 |

| ^ | 3 |

and spit out the correctly parenthesized/nested expression (1 + (2 * 3)). So nice!

But how do they work?

Bob Nystrom’s article

The original paper “Top Down Operator Precedence” (PDF or this beautiful HTML rendering) by Vaughan Pratt has a lot of theory, theorems and proofs, is somewhat philosophical at times, and spends quite some time dealing with problems of its time (1973).

Of course, as an academic paper it has a different target audience, so let’s not hold that against it. It also makes sense for it (introducing a new idea) to discuss motivation. But that makes it all the harder to find the important parts in the paper.

And I suspect that’s the reason people write summaries. You don’t need the 1973 motivation, you just need to solve the operator precedence problem!

The best summary and explanation of Pratt parsers I know of (at least for the audience of an amateur programming language designer in 2023) is written by Bob Nystrom in his blogpost “Pratt Parsers: Expression Parsing Made Easy”. You should definitely read it! (Along with other Bob’s writings, like Crafting Interpreters.)

The examples Bob gives are written in Java, and the full example implementation is split across multiple small classes.

I feel that we can do a bit better pedagogically—it can be tricky making sense of the idea when spread out like this, and it can also be challenging to port the idea from OOP to a FP language.

Not that you’d be unable to make sense of the Java code, but I see pedagogical value in trying to simplify even more.

So, that’s my motivation for writing this article! Let’s try and see how would a more minimal and concise implementation look in Elm!

Spoiler: here it is.

The language is pure, immutable, has no escape hatches, has no spooky action at a distance (eg. default arguments or exceptions) and no obscure features (except for perhaps sum types, but even those are thankfully getting more and more common in other languages).

Hence, if you can write it in Elm, you can likely write it in anything else.

Overview

The idea of Pratt parsing is very simple:

Each operator has a precedence (a number) associated with it. Larger number means higher priority, eg. multiplication has higher priority than addition.

The Pratt parser holds a precedence limit. It can be thought of as: “You’re only allowed to parse operators with precedence higher than this number.”

The precedence limit of the top-level expression is 0. Thus you could define your

expr(tokens)parser aspratt(0,tokens).

The Pratt parser first parses a prefix expression (the left part of the Op(left, op, right)), then starts a loop.

In the loop it looks at the next token. If there are no tokens left, or if it’s not a known binary operator, or if it is but its precedence is equal or lower than the limit, the parser ends and returns the left expression, alongside an information about what token to look at next (= whatever’s immediately after the left expression).

If the token is a known binary operator with higher precedence than the limit held by the Pratt parser, the parser spawns another Pratt parser with a limit equal to the operator’s precedence.

Whatever that inner Pratt parser returns (the right part of the op), the outer one combines into Op(left, op, right) which becomes the left for the next loop.

That way the Pratt parser manages to consume all operations above its limit. A Pratt parser consuming * and / will also consume ^ into a (parenthesized) child via the nested pratt(...) calls, but will never touch + and -.

…Well, that was a mouthful. Here it is in the flowchart form again:

I wouldn’t blame you if it didn’t click right away! To aid understanding, let’s examine what the algorithm does from a few different perspectives: visually, then reading through an execution trace, and then finally the code itself.

Visual intuition

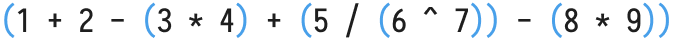

Here’s the expression we’re interested in parsing:

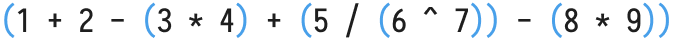

If we focus on adding parentheses (instead of tree creation), we want to end up with something similar to the following:

Let’s assign the precedence values to the operators:

| Operator | Precedence |

|---|---|

| + | 1 |

| - | 1 |

| * | 2 |

| / | 2 |

| ^ | 3 |

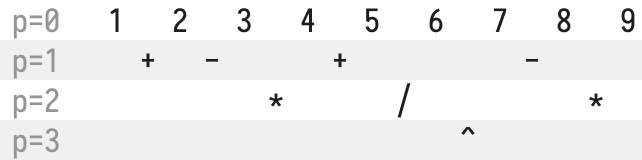

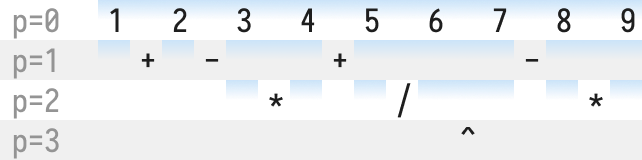

Now let’s put operators on separate lines according to their precedence:

In order to get some visual intuition on this problem, we’ll repeat a simple process on each level: given a region in a level above, we’ll draw regions between the operators on our current level:

At the very top (p=0) we’ll start with one large region:

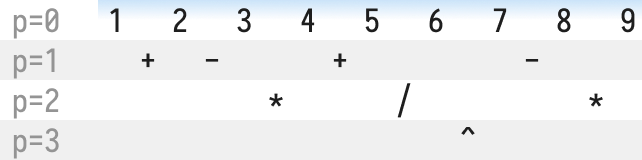

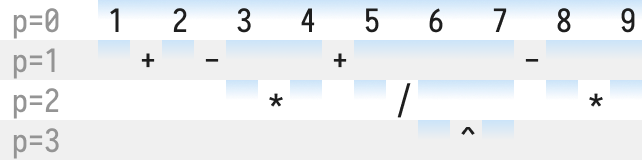

One level below (p=1), we split the region whenever we encounter an operator on our level—that is, + or -.

Continuing on to p=2, we’ll split each blue region when we find * or /.

To make the diagram less cluttered, we’ll skip processing regions with single numbers, eg. here

1and2.

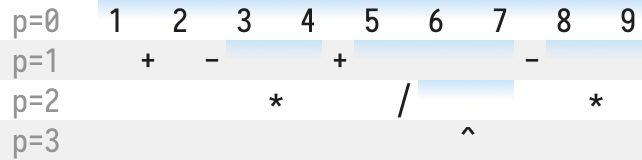

And then finally on level p=3 we split the region containing the ^.

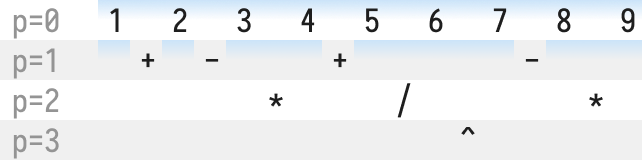

By now perhaps you already see what’s happening: each blue region represents a set of parentheses!

Let’s clean the diagram up a little before we show that off: parentheses with no operators inside aren’t very helpful (eg. (3) vs 3), so we’ll remove the blue regions that only hold single numbers:

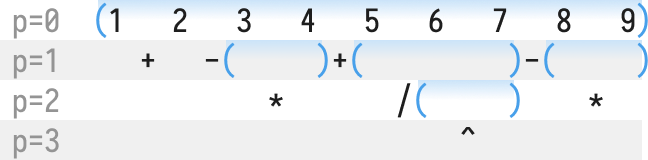

And now we can finally replace each beginning of a blue region with ( and each end with ):

Merging each level into the one above, we end up with the parenthesized expression we wanted:

What we have been doing visually, corresponds to the Pratt parser algorithm: the blue regions on level p=n are calls to the pratt(n) parser. (Except for the leftmost numbers of each block, which are handled by the prefix parser.)

Let’s now walk through the algorithm on an example to see that. (I swear there’s going to be some code in this blogpost eventually.)

Walk-through example

The source we’re trying to parse is 1+2-3*4+5/6^7-8*9.

It corresponds to a sequence of tokens:

[ 1, +, 2, -, 3, *, 4, +, 5, /, 6, ^, 7, -, 8, *, 9 ]

The precedences are as follows:

| Operator | Precedence |

|---|---|

| + | 1 |

| - | 1 |

| * | 2 |

| / | 2 |

| ^ | 3 |

In this simplified example, there are no unary operators. We’ll talk about those near the end of the blogpost.

Step through the execution to see what’s happening:

Elm implementation

Hopefully you noticed the parallels between the visual interpretation and the flowchart’s recursive descent down the stack frames.

Each Pratt parser is able to handle a single precedence level and delegate the higher levels to child Pratt parsers, while refusing to do anything for lower levels.

Well, let’s formalize what we just went through!

First, let’s define the types we’ll work with.

type Token

= TNum Int

| TOp Binop

type Binop

= Add

| Sub

| Mul

| Div

| Pow

type Expr

= Num Int

| Op Expr Binop Expr

Our token list and operator precedence table:

exampleTokens : List Token

exampleTokens =

[ TNum 1

, TOp Add

, TNum 2

, TOp Sub

, TNum 3

, TOp Mul

, TNum 4

, TOp Add

, TNum 5

, TOp Div

, TNum 6

, TOp Pow

, TNum 7

, TOp Sub

, TNum 8

, TOp Mul

, TNum 9

]

precedence : Binop -> Int

precedence binop =

case binop of

Add -> 1

Sub -> 1

Mul -> 2

Div -> 2

Pow -> 3

And now, the fun begins.

parse : List Token -> Maybe Expr

parse tokens =

case pratt 0 tokens of

Just ( expr, tokensAfterExpr ) -> Just expr

Nothing -> Nothing

The top-level parser calls pratt 0 and then throws away the tokens it returns (only keeps the parsed expression).

We’ll get some preliminaries out of the way:

prefix : List Token -> Maybe (Expr, List Token)

prefix tokens =

case tokens of

[] -> Nothing

(TNum n) :: rest -> Just ( Num n, rest )

(TOp _) :: _ -> Nothing

Note that in a more advanced language you’d probably have prefix operations like negation (

-5) or explicit grouping via parentheses ((5+3)). We’ll talk about these near the end of the blogpost.

pratt : Int -> List Token -> Maybe (Expr, List Token)

pratt precLimit tokens =

-- First parse a prefix expression

case prefix tokens of

Nothing -> Nothing

Just ( left, tokensAfterPrefix ) ->

prattLoop precLimit left tokensAfterPrefix

prattLoop : Int -> Expr -> List Token -> Maybe (Expr, List Token)

prattLoop precLimit left tokensAfterLeft =

-- The next token is an operator! Let's find its precedence.

case tokensAfterLeft of

-- Operator!

(TOp op) :: tokensAfterOp ->

let

opPrec : Int

opPrec = precedence op

in

-- Now, are we allowed to parse the next expression

-- or is it outside the limit?

if opPrec > precLimit then

-- We can parse it! Spawn a child Pratt parser.

case pratt opPrec tokensAfterOp of

-- Whatever the child Pratt parser did,

-- we take it and combine it with our `left`.

Just ( right, tokensAfterChild ) ->

let

newLeft : Expr

newLeft = Op op left right

in

-- There might be more on our level

-- (like in 1+2-3), so let's loop.

prattLoop

precLimit

newLeft

tokensAfterChild

-- An error, propagate it.

Nothing -> Nothing

else

-- We shouldn't parse this op.

-- Return what we have.

-- (Note our token list points at the op,

-- not at the token after.)

Just ( left, tokensAfterLeft )

-- Either we ran out of tokens or found something

-- that's not an operator. Let's return what we have.

_ -> Just ( left, tokensAfterLeft )

And that’s all!

Running this—either in the elm repl or in the browser with something like:

module Main exposing (main)

import Html

main =

parse exampleTokens

|> Debug.toString

|> Html.text

—will result in:

Just (Op (Op (Op (Op (Num 1) Add (Num 2))

Sub

(Op (Num 3) Mul (Num 4)))

Add

(Op (Num 5)

Div

(Op (Num 6) Pow (Num 7))))

Sub

(Op (Num 8) Mul (Num 9)))

as you can see in the Ellie with the full source.

This can with some elbow grease be translated into:

((((1 + 2) - (3 * 4)) + (5 / (6 ^ 7))) - (8 * 9))

and if you remove parentheses around pluses and minuses, you’ll get our wanted result:

1 + 2 - (3 * 4) + (5 / (6 ^ 7)) - (8 * 9)

Parsing successful!

Loose threads

The above illustrates the core idea Pratt parsers on left-associative binary operators, but that isn’t enough for real-world languages. There are a few unanswered questions. Let’s answer them:

Right-associativity

What about right-associativity? ^ is right-associative, meaning 2^3^4 should parse into 2^(3^4).

Thankfully this is simple to solve: each operator will now have an isRightAssociative boolean associated with it in addition to the precedence level.

When the pratt function gets that boolean, it will calculate the precedence this way:

opPrec : Int

opPrec = precedence op

finalPrec : Int

finalPrec =

if isRightAssociative op then

opPrec - 1

else

opPrec

Then you need to use opPrec for the condition and finalPrec for the recursive call:

if opPrec > precLimit then

case pratt finalPrec tokensAfterOp of

...

And that’s it!

Here’s a runnable example with right associativity, parsing 1^2^3+4 into (1^(2^3))+4: Ellie.

More complex prefix expressions

In our example we only had numbers as the prefix expressions. What if we wanted negation and parentheses?

Let’s add a few new tokens to illustrate:

type Token

= TNum Int

| TOp Binop

| TLeftParen -- new

| TRightParen -- new

We’ll reuse TOp Sub for negation; normally you’d have tokens like Minus and Plus rather than assigning them meaning during lexing.

This is how the new prefix parser would look:

prefix : List Token -> Maybe (Expr, List Token)

prefix tokens =

case tokens of

[] -> Nothing

(TNum n) :: rest -> Just ( Num n, rest )

-- negation, consumes two tokens

(TOp Sub) :: (TNum n) :: rest ->

Just ( Num (negate n), rest )

-- left paren: consumes '(', an expression, ')'

TLeftParen :: rest -> groupedExpr rest

-- right paren: doesn't make sense on its own

TRightParen :: _ -> Nothing

(TOp _) :: _ -> Nothing

groupedExpr : List Token -> Maybe (Expr, List Token)

groupedExpr tokens =

-- Has consumed TLeftParen already

case pratt 0 tokens of

Nothing -> Nothing

Just (expr, tokensAfterExpr) ->

case tokensAfterExpr of

-- A closing paren must follow

TRightParen :: rest -> Just (expr, rest)

-- Unbalanced parens!

_ -> Nothing

Postfix expressions

How to make Pratt parsers support postfix operators, like i++ or 5!?

These are a special case of infix operators:

Postfix expressions need the prefix expression parsed and the operator consumed, but they don’t need to consume any right part. Thus there would be one less pratt call for the right-hand side.

Postfix expressions are admittedly where I simplified my explanations too much. The Pratt parser really cares about two classes of operators: prefix, and anything else.

In the above Elm code I’ve baked the assumption we’ll only deal prefix and infix (binary), into the pratt function itself. In reality each operator token would have a parser associated with it that deals with whatever’s after the operator, and the pratt function would call that.

{-|

Example: 5+3

Token expectations:

expr op expr

^^^^^^^ already parsed

-}

binaryOp : Expr -> Binop -> Int -> List Token -> Maybe (Expr, List Token)

binaryOp left op precedence tokensAfterOp =

-- what we had before in `pratt`, just extracted into its own function

case pratt precedence tokensAfterOp of

Nothing -> Nothing

Just (right, tokensAfterRight) ->

Just (Op left op right, tokensAfterRight)

which then gives us the freedom to write postfix parsers. With some handwaving they could look like:

{-|

Example: 5!

Token expectations:

expr Bang

^^^^^^^^^ already parsed

-}

postfixBang : Expr -> Binop -> List Token -> Maybe (Expr, List Token)

postfixBang left op tokensAfterOp =

-- We're guaranteed to have parsed the `!` already

-- Nothing to do here!

Just (UnaryOp Factorial left, tokensAfterOp)

Conclusion

Pratt parsers are nice in that they let you define a table of operators and their precedence levels, which they then work through: the traversal itself is abstracted away.

Pratt parsers can be shrouded in mystery (particularly if you encounter terms like nud and led while reading about them or using a library that didn’t care to find better names).

With that in mind I hope I have demystified this technique a little bit and made you consider using or writing one. Life’s too short to deal with operator precedence in an ad-hoc way!